Japanese anime has taken the world by storm, and India is no exception. In September 2024, the capital city of New Delhi hosted “Mela! Mela! Anime Japan!!” (MMAJ), the first major event dedicated to promoting Japanese anime to Indian consumers. The event returned for a second run in September 2025, where the latest Crayon Shin-chan film set in India, “Crayon Shin-chan: The Spicy Kasukabe Dancers in India,” drew massive crowds and enthusiasm.

Behind this growing anime wave are shows like Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan, both of which have become household names across India. According to a recent report released by JETRO, Japanese animation has moved beyond niche fandom in India and is increasingly becoming part of everyday popular culture, driven by long-running franchises, consistent broadcasting, and deep localization efforts.

India Is A Key Market Since 2005

TV Asahi first entered the Indian market in 2005 with Doraemon. While the company’s international reach covered Europe, the US, and India, According to executives from TV Asahi’s International Business Development division, India has remained a priority territory due to its large youth population and long-term growth potential.

Doraemon began airing on Japanese TV in 1979, while Crayon Shin-chan started in 1992. Both shows have accumulated thousands of episodes over the decades and continue to release new episodes weekly in Japan even today.

In India, Doraemon started broadcasting in 2005, followed by Crayon Shin-chan in 2006. That gives both shows nearly 20 years of presence in the country. According to executives, three factors contributed to their success in India:

- Abundant episode count: With thousands of episodes available, there’s always fresh content to offer.

- Long broadcasting history: Nearly two decades of consistent presence built familiarity and trust.

- Large young population: As of July 2024, India has around 230 million people aged 10 and under, roughly double Japan’s entire population.

These three elements combined to create the perfect environment for anime to thrive.

Anime Boom Coincided With TV Expansion

Executives pointed out that the timing of Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan’s launch in India aligned perfectly with the country’s television boom. This wasn’t a coincidence; it was a critical advantage.

In 2000, the Indian government officially allowed Direct-to-Home (DTH) broadcasting services, which had been banned until then. DTH allows satellite TV signals to be received directly by households without needing cable infrastructure. By 2003, digital terrestrial broadcasting started, bringing high-quality TV access even to rural areas that cables couldn’t reach. Television ownership spread rapidly across India during this period.

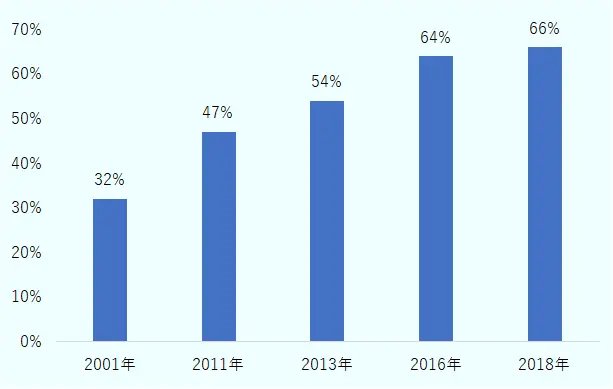

Data from BARC India (Broadcast Audience Research Council) shows that TV ownership in Indian households grew steadily:

- 2001: 32%

- 2011: 47%

- 2013: 54%

- 2016: 64%

- 2018: 66%

The rise in TV ownership directly supported the expansion of anime viewership. As more families gained access to television, more children were exposed to Japanese anime during their formative years.

Continuity, Themes, and Localization

In Japan, anime isn’t just for kids. People in their 20s and 30s continue watching anime well into adulthood. India is showing similar patterns, especially with long-running shows like Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan. According to the executives, keeping anime relevant across generations requires building habits early and maintaining them as viewers grow.

They outlined three reasons why these anime continue to resonate with Indian audiences across age groups.

1. Continuity

Both shows are still being produced in Japan. That means there’s a constant supply of new content. If a show ends, broadcasters are limited to old episodes, and eventually, they run out of material to sell. In India, new episodes are more popular than older ones. Delivering fresh content consistently is essential for keeping anime culturally relevant.

2. Universal Themes

Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan focus on everyday life. School routines, family dinners, small adventures, moments of emotion, all of these are woven into relatable, mundane settings. For instance, going to school, studying, eating meals with family, and having conversations are daily experiences that Indian children can connect with. The themes aren’t exotic or distant. They reflect values and habits that exist in India as much as they do in Japan.

3. Localization

Localisation is about more than just translation. Executives from TV Asahi stressed two key aspects of effective localization.

First, careful dubbing in local languages. India has 22 officially recognized languages, including Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu. To make anime a habit for children, dubbing into regional languages is non-negotiable. But it’s not just about translating words. The process involves “adaptation,” where dialogues are adjusted to fit Indian cultural nuances and humour, rather than being literal translations from Japanese.

Second, strong partnerships with local companies. TV Asahi creates the programs, but local partner companies handle dubbing, cultural adaptation, and scheduling. They know when children are most likely to watch, usually mornings and evenings, and they organize programming around those windows. The success of Japanese anime in India depends heavily on these partnerships.

Co-Production is Accelerating

For nearly 30 years, TV Asahi primarily exported finished anime episodes to international markets. But recently, the company has shifted toward co-producing new content with local partners, according to both Inaba and Sumida.

Exporting finished products is more efficient and profitable. Co-production, on the other hand, takes more time, effort, and coordination. It requires aligning creative visions between Japanese and local teams. But despite the challenges, co-production offers something exports don’t: deeper engagement, creative fulfillment, and opportunities to train younger staff members in cross-cultural collaboration.

In August 2025, a co-produced version of “Obocchama-kun,” a popular Japanese anime from the late 1980s, began airing in India. Sumida (an executive from TV Asahi), who worked on the project, highlighted just how important adaptation is in these collaborations.

Obocchama-kun relies heavily on Japanese wordplay and puns to generate humour. Direct translation doesn’t work because the jokes lose their meaning in another language. The team had to rewrite jokes to fit Indian cultural references and humour styles. The goal, Sumida explained, is to make Indian children think, “Is this really a Japanese anime? I thought it was made in India.“

The production methods also differ between the two countries. Japan traditionally uses hand-drawn animation, while India relies more on digital animation. This creates technical challenges, especially when trying to convey depth and dimension in scenes. On top of that, humour itself doesn’t always translate. Sumida shared an example: in one episode, the main character becomes pregnant. Japanese audiences found the absurdity funny, but Indian audiences didn’t get the joke at all. The teams had to sit down and discuss what humour works in each culture and why.

Creating content with a local company requires effort, creativity, and flexibility. But Inaba sees it as more than a business transaction. She intentionally assigns younger employees to these co-production projects. The experience they gain working across cultures and navigating creative differences is invaluable. For her, the real return isn’t just revenue. It’s the deepened relationships with local partners and the confidence it builds in her team.

Fighting Piracy and Counterfeit Goods

In recent years, illegal manga upload sites and pirated anime streams have become a growing problem. For content companies, protecting intellectual property is essential. TV Asahi uses AI-powered patrol systems to detect and flag suspicious videos that may violate copyright. The company also responds to reports of counterfeit merchandise sold locally in India.

Both Inaba and Sumida stressed that staying vigilant is necessary. They can’t afford to give counterfeit goods or pirated content any space to operate. The fight against piracy is ongoing, and it requires constant monitoring.

The “TV Asahi 360°” Strategy

India’s entertainment market is growing fast. Anime, manga, and gaming content are expanding at an incredible pace. TV Asahi knows it needs to evolve its IP (Intellectual Property, meaning characters and franchises that can be used across different media) business strategy to keep up.

Sumida referenced the company’s mid-term management plan for 2023-2025, called “TV Asahi 360°.” The name reflects a shift in how the company thinks about content. Previously, TV Asahi focused mainly on broadcasting TV programs. But today, the possibilities have expanded. Movies, merchandise, live experiences, theme parks, all of these are now part of the strategy.

In line with this vision, TV Asahi is opening a new entertainment complex in Tokyo’s Ariake district on March 27, 2026, called “Tokyo Dream Park.” The facility will offer immersive experiences tied to the company’s IP, extending anime beyond the screen and into physical spaces where fans can interact with their favourite characters.

The anime industry is changing, and TV Asahi is determined to stay ahead. As Sumida put it, the company must continue applying the 360° strategy not just in Japan, but in every country and region where it operates, including India.

Japanese anime didn’t succeed in India by accident. It took the right content, the right timing, and the right partnerships. TV Asahi’s approach, rooted in continuity, cultural sensitivity, and collaboration, offers a blueprint for how entertainment can cross borders and build lasting connections.

Source: JETRO